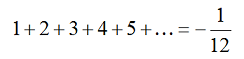

Recently, quite by accident I discovered this fact:

If you are a social network user (like a normal individual) you probably became aware of this “equality” through the by now viral video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w-I6XTVZXww. If you don’t use the social webz very much (like me) this might be the first time you’re seeing it (although, you might have found out about the video through the twitter announcement of this blog post, in which case, never mind). Go ahead, stare at it again. I’ll make it easy for you:

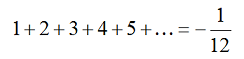

I know, right? If you studied divergent series in colleges you are probably squirming in your seat and starting to enter a deep state of denial and thinking “How can he make such a preposterous claim?” Allow me to do so again:

Don’t worry I haven’t forgotten my math. The above expression, although valid, is not actually a true equality, at least not in the same formal sense that 1+ 1=2. In fact, it’s not even a new expression. It has been known since the mid-1800s and a mathematician named Srinivasa Ramanujan was (arguably) the first to arrive at the odd value of -1/12 using a strange type of summation that allows one to assign a value to divergent series. Another way to get at the result is using the super cool Riemman zeta function Z(s): Z(-1) = – 1/12.

After finding out about this surprising result I went to investigate and discovered a whole branch of complex analysis dedicated to obtaining results like this one. Using something called analytic continuation it is possible to extend the domain of some functions to regions where they not originally defined – a process you might call mathematical suspension of disbelief. It does so by redefining some of the basic high-school algebra rules. What this means is that, while analytic continuation produces perfectly logical and self-consistent results, they are not directly relatable to “real-world“ mathematics.

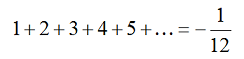

What at first seems just some number mumbo-jumbo made to wow audiences is in fact a technique with many applications in science. The particular expression showcased here is used in string theory and quantum electrodynamics. In 1971, Martinus J.G. Veltman and Gerardus 't Hooft, respectively professor and then graduate student in theoretical physics, used analytic continuation methods to renormalize Yang-Mills theory (particle physics stuff), a feat that would earn them the Nobel Prize in 1999. Only by ignoring divergences in intermediate calculations and daring to extend the validity of their expressions were they able to come to a final result with real-world applicability.

Simply put, there is nothing you can do with a value of “infinity”. It ends your calculations, it keeps theories stuck and it can’t be observed or otherwise measured. In short, infinities do not exist except in mathematicians’ idealizations. So, clever humans that we are, we found a way around them: by replacing infinities with logical, self-consistent and much more useful values like the one from the above sum we can overcome difficulties in our calculations and try to advance the limits of human knowledge.

While mathematics can be used create wonderful tools for science, it is not, in itself a science. I like to think of it as an art form – The art of creating beautiful, logical statements that need not have a concrete “physical” representation. Science is about the study of reality and as such if you find yourself proving that gravity is infinite at some point in space, speed is instantaneous or the number of universes is infinite, please do go back and re-check the tools you used. You may find that all you need is a little suspension of disbelief to come to the ultimate truth.