This piece was originally published in the Daily Northwestern

Rebecca Blank is Northwestern’s next university president, and some of the expectations for the role have not changed that significantly over the University’s 170-year history.

Just as was asked of Clark Hinman and Henry Noyes, President-elect Blank is expected to keep a sharp focus on growing the $14 billion endowment. A novel aspect of the president’s role, however — one that did not truly exist until the mid 1980s — is climbing the national rankings. Research strongly suggests that ranking and endowment growth are strongly correlated at elite private universities and have become the focus of both presidents and boards of trustees at those institutions.

By both these measures, NU has been doing extraordinarily well. In remarks to faculty, University President Morton Schapiro has frequently highlighted the success of the We Will campaign, which fundraised over $5.3 billion. Similarly, NU rose in the rankings from 12 to nine during his tenure.

Even so, President-elect Blank should not pursue the current strategic focus on national rankings. Instead, we need a more balanced approach to investing in the academic mission of the University.

The focus on rankings hides numerous issues regarding how they are determined and what they measure. If rankings were not noisy measures, then one would not expect to see some of the inconsistencies that occur year over year.

Additionally, the emphasis on endowment growth creates tension with other goals. As the portion of funds raised and placed in the endowment increases, the fraction that can be used to, for example, create more opportunities for scholarly endeavors or for maintaining and growing critical infrastructure, decreases.

To provide a more informed understanding of NU’s current national rank and assess whether our focus should be on rising in the rankings, it’s important to provide some background on how rankings change over time and whether improvements truly signify institutional change.

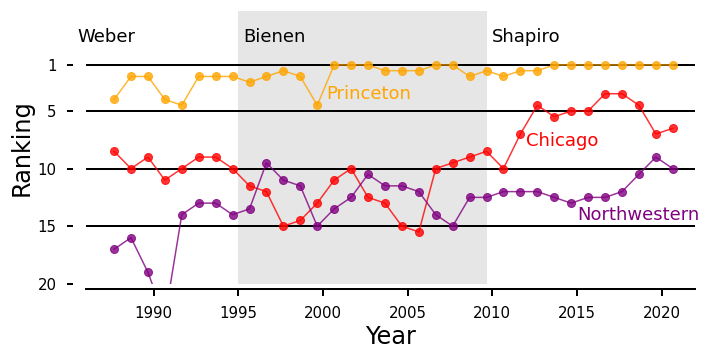

Considering all the celebration about reaching a rank of nine, it may be surprising to find out that during the past 30 years the University’s ranking has been fluctuating between 15 and 10, with the occasional breakthrough to nine.

Figure 1. Temporal evolution of the rankings of Princeton University, University of Chicago, and Northwestern University. U.S. News and World Report rankings released in September 2020 are named the 2021 rankings. Instead, I assign the ranking of a university to the date it was released. A misleading feature of most ranking systems is that if two universities are tied, both are granted the higher ranking. For example, in the latest rankings Northwestern was in a 3-way tie with Johns Hopkins and CalTech. While this choice is flattering to all the universities involved, it does not make much sense. Being the sole owner of first is clearly better than being tied with another university for first, which is, in turn, better than being tied for first with two other universities. To account for this reality, I assign to each tied university not the highest ranking but the average of the set of ranks that would have been used if there had not been a tie.

In view of the noisiness of rankings, maybe it is more fruitful to ask not what our current ranking is, but whether there has been an improving trend in NU’s ranking. Those familiar with statistical analysis will immediately ask if we can detect a statistically significant linear trend in NU’s rankings.

Looking at the entire period, the answer is probably yes. If we consider only the post-1992 period, however, after the financial issues experienced during the Strotz presidency had been addressed, the answer is likely no. And, if looking only at the Bienen and Schapiro presidencies, then the answer is a definite no.

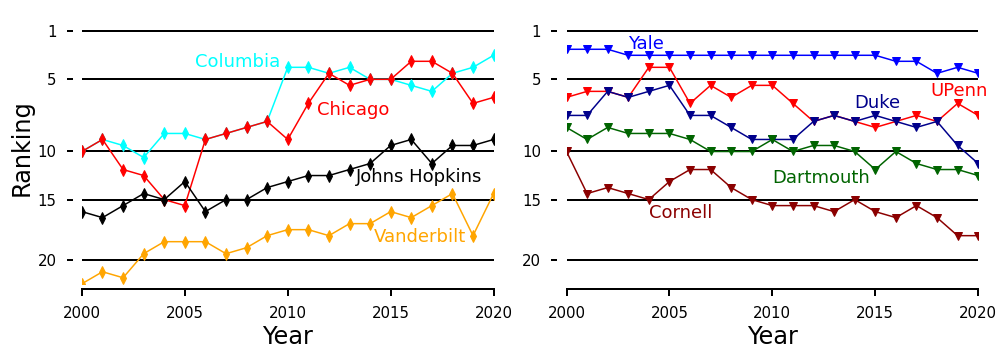

The data visually suggest that the University of Chicago’s ranking has risen during the same period. To further investigate this possibility, I considered all private universities that have been consistently ranked in the top 20 since 2000 and identified those for which there is a significant linear trend in their ranking. Four universities — Columbia University, University of Chicago, Johns Hopkins University and Vanderbilt University — have significantly improved their rankings. Seven universities — Yale University, University of Pennsylvania, Duke University, California Institute of Technology, Dartmouth College, Washington University in St. Louis and Cornell University — have significantly lost prestige. What could be behind these changes?

Figure 2. Temporal evolution of the top-twenty private universities whose ranking has changed significantly over the past twenty years.

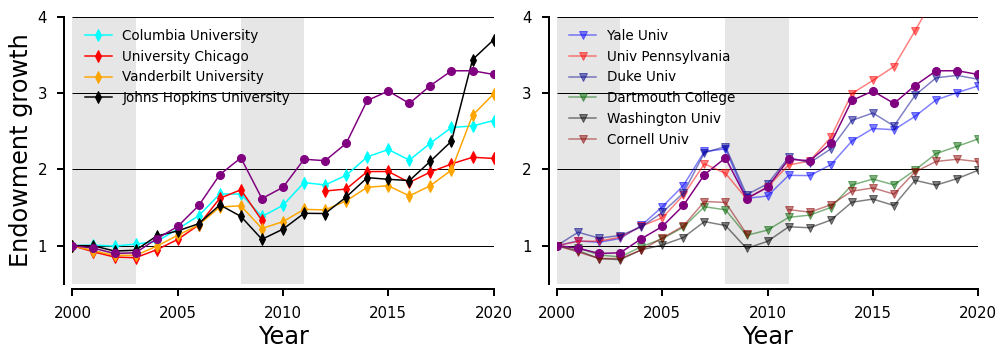

To attempt to answer this question, I look at the other measure that boards of trustees monitor closely: endowment growth in Figure 3. A plausible hypothesis, according to the research literature, is the rising universities experienced greater growth of their endowment than the declining ones. Because actual endowment sizes can vary so much and because of the widely different sizes of the alumni population of these universities, I show the post-2000 endowment growth of several of these 11 universities.

Clearly, I do not have enough data here for making statistically significant determinations. Nonetheless, a few features appear worthwhile to note. First, the endowment growth of the highest ranked declining universities — Yale, UPenn and Duke — was higher than the growth for the four rising universities.

Figure 3. Endowment growth since 2000 of NU (purple circles and line) and nine universities whose ranking has changed significantly over the past twenty years. The gray shaded areas highlight the impacts of the 2000 stock market crash and the 2008 financial crisis.

Strangely, the big endowment gain by Vanderbilt in 2019 was contemporaneous with a large negative fluctuation in its ranking. Second, NU’s endowment grew significantly faster than the endowments of six out of the seven declining universities. Third, for most of the considered period, NU’s endowment also grew significantly faster than the endowments of the four rising universities.

All these universities considered have had at least one successful fundraising campaign since 2000 and have closely followed the investment strategy promoted by Yale’s investment team. This raises the intriguing possibility that the reason why the endowment of the rising universities has grown slower is that they have invested more of the raised funds into academic growth rather than endowment growth.

Columbia, in particular, seems to have made sizable investments into a number of new strategic areas (neuroscience, free speech, data science and climate change). Could NU’s ranking have actually risen if, for example, the $800 million surplus of a few years ago had been invested in research infrastructure instead of added to the endowment?

In any case, whether more ambitious investments in research infrastructure increase the rankings, they do have the potential to improve the work of faculty and graduate students, and the academic experiences of undergraduate students. Indeed, they could even contribute to help local communities respond to societal challenges such as addiction, gun violence or climate change. As was recently reported in The New Yorker, Columbia faculty are having a direct impact on the manner in which New York City will respond to the challenges posed by climate change.

It is a wonderful feeling to be a member of a leading university. It is an even better one to truly deserve the honor. With the selection of a new president, NU has the opportunity to reinvest in academic growth and to claim true leadership among its peer institutions. Doing so might lead to an improved ranking, but it would, more importantly, directly improve our research, teaching and contribution to society.