In 2009, Lazer et al. wrote about a field with enormous potential that still faced numerous obstacles. In 2012, Giles wrote about a field attracting ever-increasing numbers of scientists and spawning creation of new academic departments. In 2018, computational social science is coming into its own.

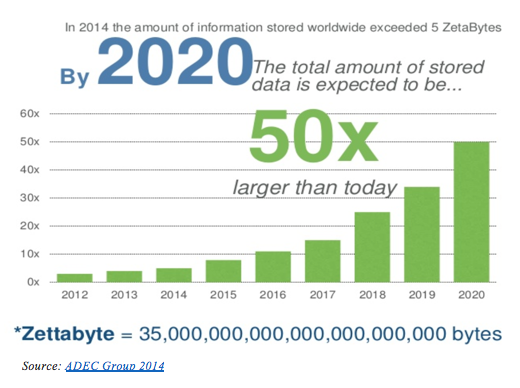

Computational Social Science has become possible thanks to the digital age. This integration of technology into our daily lives has generated an enormous amount of data.1 The scale of this data is so large that it presents an unprecedented opportunity to study complex social behaviors.2 Adoption of computational social science has been rapid. Thousands of papers have been published in top journals, international conferences have been established, and universities are actively hiring computational social scientists. At the same time, financial commitments from companies like Facebook and social science grant initiatives like the Russell Sage Foundation have begun to facilitate interdisciplinary boundary crossing of computational social science.3 New institutes like the Summer Institute for Computational Social Science bring together computer scientists, statisticians, and social scientists for interdisciplinary learning and projects.

The advent of computational social science presents a unique opportunity for computer scientists, statisticians and social scientists to collaborate. It would be falsely reductionist to say that a sociologist who uses python is automatically a computational social scientist. It would be similarly misleading to simply designate all computer scientists interested in social phenomena computational social scientists. Cornell computer science professor Jon Kleinberg4 epitomizes this junction saying, “I realized that computer science is not just about technology…It is also a human topic.”

Princeton sociologist Matt Salganik helps make sense of this combination in his new instructional text Bit by Bit: Social Research in the Digital Age] Salganik identifies two primary misconceptions on the parts of both data scientists (among them computer scientists and statisticians) and social scientists on the contributions of their counterparts. First, he takes data scientists to task for the assumption that more data is a solution to any problem. While increasing sample sizes is often helpful, sometimes we need new data types rather than more of what we already have access to. A second misconception among data scientists is writing off social science as common sense. Assuming common sense over a carefully investigated and theory motivated analysis of human behavior obscures the phenomena of investigation.

Social scientists are not without their own obstacles to overcome. Salganik notes that social scientists might be especially prone to dismissing digital data on the basis of a few bad papers. Salganik identifies a related pitfall: not fully conceptualizing the future of computational science and digital data. As we advance into the digital age this type of data will continue to grow and become more integrated in the lives of society, making it necessary for social science disciplines to take it into account. A true collaboration across social scientists and computational scientists will not only produce methodological stronger research, but it will also make it possible to study things neither could study alone.

Want to learn more? Click here to learn about the Summer Institute for Computational Social Science. Click here to look at the SICSS 2017 GitHub. Click here to read cutting edge computational social science from the Amaral Lab. If you’re in the Chicago area, stay tuned: some exciting computational social science news is coming soon!

References

1 Conte, Rosaria, et al. “Manifesto of computational social science.” European Physical Journal-Special Topics 214 (2012): p-325.

2 Lazer, David, et al. “Life in the network: the coming age of computational social science.” Science (New York, NY)323.5915 (2009): 721.

3 Watts, Duncan J. “Computational social science: Exciting progress and future directions.” The Bridge on Frontiers of Engineering 43.4 (2013): 5-10.

4 Giles, Jim. “Making the links.” Nature 488.7412 (2012): 448-450

5 Salganik, Matthew J. Bit by bit: social research in the digital age. Princeton University Press, 2017.